| Equity investing can be a complex business. The variables at play are numerous – not just the macro and micro variables relevant to a stock, but also the psychological factors facing an investor. Maths, Science and Art are subjects that have improved our ability to understand the complexities of the world around us. Whilst decisions based on myths or one’s personal beliefs exposes an investor to more luck than skill, a rigorous hunt for mathematical and scientific tools helps the investor reduce the contribution of luck and enhance the probability of success. In fact, rigorous tools are the key factor which allow a small minority of investors to attain the objective of Consistent Compounding (even as the vast majority of investors live life at the mercy of Lady Luck).

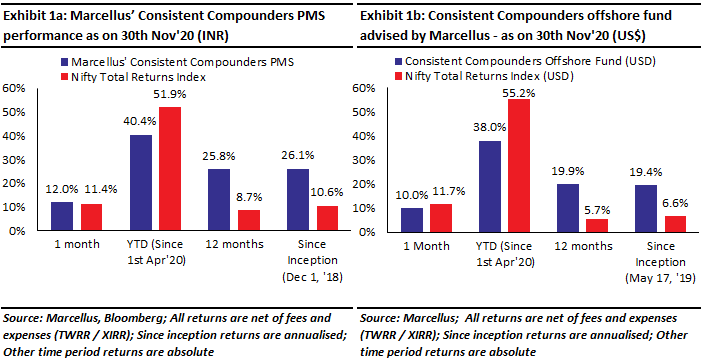

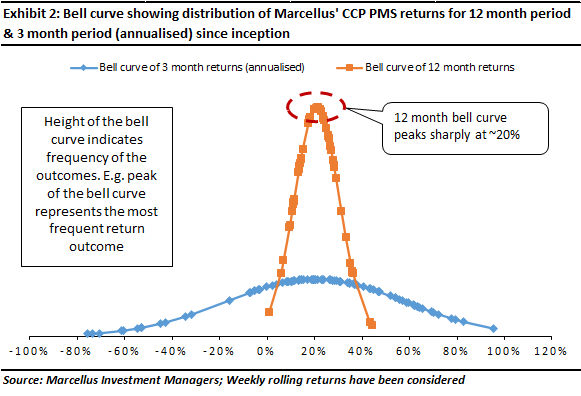

Performance update – as on 30th November 2020

We have a coverage universe of around 25 stocks, which have historically delivered a high degree of consistency in ROCE and revenue growth rates. Our research team of eleven analysts focuses on understanding the reasons why companies in our coverage universe have consistently delivered superior financial performance. Based on this understanding, we construct a concentrated portfolio of companies with an intended average holding period of stocks of 8-10 years or longer. The latest performance of our PMS and offshore fund (USD denominated) portfolios is shown in the charts below.

The Maths, Science and Art of investing in equities (and hence in Consistent Compounders)

“The most beautiful thing we can experience is the mysterious. It is the source of all true art and all science. He to whom this emotion is a stranger, who can no longer pause to wonder and stand rapt in awe, is as good as dead: his eyes are closed.” – Albert Einstein

There are several mysteries that an investor faces while deciding which stocks to buy, and when to buy (or sell). For any listed company there are several variables at play – external events like macroeconomic variables, competition, disruptions, FII / DII flows; or company specific events like valuations, change in management, capital allocation decisions; or personal factors such as the investor’s purchase price (and hence unrealised gains or losses currently), capital gains tax liability, risk appetite, financial goals and hence expected returns etc.

The only rational method than can help an investor navigate through this maze of variables is by making extensive and rigorous use of tools in the domain of Maths, Science and Art. Investors who don’t use such tools extensively to arrive at a high degree of clarity of thought, expose themselves substantially to ‘luck’ as the driver of their investment outcome.

Let’s illustrate by taking an example of two farmers who have paddy fields adjacent to each other. The first farmer believes that since rainfall is an unpredictable variable (and one that is controlled by the Gods), there is no point in slogging it out on the paddy field beyond a point. The first farmer’s motto is “When the Rain Gods smile on us, we have a good year. Otherwise we struggle.” In contrast, the second farmer studies the soil type, assesses climactic conditions and then conducts research on the most appropriate type of paddy to plant in such conditions. As a result, even when the rainfall is deficient, the second farmer is able to get a decent crop by planting seeds which need less water. The second farmer’s motto is “My job is to optimise all the variables that are in my control so that even when the rains fail, I can put food on the table for my family.” Investors who use rational tools based on Maths & Science are like this second farmer whilst investors who believe in luck and irrational judgements are like the first farmer. Let’s now discuss some of our favourite Maths based tools.

The simplest form of Maths uses logic that cannot be debated against and that does not change over time. In equities, Maths not only helps us bust psychological myths, but also helps us focus only on the relevant factors in the investment process. Some of the most common examples include:

- The power compounding: Albert Einstein is credited with the statement “Compound interest is the eighth wonder of the world. He who understands it, earns it…. He who doesn’t… pays it”. This is perhaps the most powerful mathematical tool that an investor needs to understand, in order to maintain discipline and focus, no matter how boring that might make the investing journey.

- P/E multiple: A little bit of thinking about the equation P = P/E * E helps suggests that for investors who want to buy and hold high quality stocks, their focus should only be on the compounding factor in the equation i.e. earnings, and not on the non-compounding factor in the equation i.e. P/E multiple.

- ROCE, reinvestment rate and earnings growth: The ability to sustain 30% ROCE with high proportion of capital reinvestment delivers better earnings growth compared to 100% ROCE without any capital reinvestment.

- Profit booking: The concept of ‘Profit Booking’ makes no logical sense in a portfolio of high quality stocks – as explained in our November 2020 webinar on this subject (click here)

- Pricing power vs price hikes: High pricing power doesn’t only relate to the ability to hike product prices without losing market share. It also relates to the ability to avoid price cuts in the face of a price war without losing market share – as we explained in our June 2020 recent newsletter (click here).

- ‘Purchase price’ does not matter: An investor’s decision to continue holding an existing stock in their portfolio should NOT depend on whether their purchase price was substantially higher or substantially lower than today’s price. For instance, a bad investment should not be held in a portfolio because the investor bought the stock at a very cheap price.

- Absolute valuation: A stock can be expensive at 10x P/E multiple, and another stock can be cheap at 50x P/E multiple. Also, the logistical impact of events like demonetisation and Covid-19 lockdowns on a couple of quarters’ cash flows should have no bearing on a stock’s fair valuation as long as the cash flow compounding engine remains unchanged in the longer term.

- Impact of transaction costs and capital gains tax on the power of compounding: A simple mathematical exercise can help an investor understand the demerits of high churn, profit booking and various other expenses involved in equities investing. Quantification of this can also be found in the book ‘Coffee Can Investing: the Low Risk Route to Stupendous Wealth’ (2018) – Chapter 3.

- Bonus shares: Issue of bonus shares does not help investors (barring maybe reducing the ticket-size to attract small investments, or some possible capital gains tax benefits) because all it is doing is cutting the same pizza into smaller pieces.

The concepts of ‘Science’ and ‘Art’ are different from Mathematical concepts. Science and Art can be debated against and they can change / evolve over time. Obviously, Science and Art are very different from each other. Science is analytical, Art is intuitive. Science is logical, Art is creative. Science is objective, Art is subjective. Artists depend mostly on their thoughts, ideas and personal views for their work. On the other hand, scientists base their work on natural laws, facts, available information, and how to fit their informed ideas into these laws to creatively invent or discover something. The imagination of a scientist is based on reality. A scientist needs to get his imagination right to succeed. On the other hand, usually there are no ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ answers in art. Most importantly, elements of Science and Art can be mastered to develop skills that help resolve a mystery in a manner, better than one’s peers.

When it comes to equities, the lack of deep understanding of the fundamentals of a stock or of an investment philosophy makes the approach more ‘artistic’ than ‘scientific’. This then reduces the probability of success in decision-making process that investors follow. Several great investors / research analysts have come out with frameworks for their scientific approach, which can be used by others to deepen their fundamental understanding. Some areas of scientific approach / frameworks in equities include:

- Industry growth drivers: Understanding the nature, quantum and longevity of growth drivers of an industry is an integral part of research on a company operating in that industry. Michael Porter’s ‘Five Forces’ framework is one of the tools that help deepen this understanding. These aspects evolve as demographics, customer tastes and preferences, technology etc changes over time.

- Cash generative competitive advantages of a firm: This is perhaps the deepest aspect of fundamentals-based equities investing. Who is the real customer (not necessarily the end customer) of the firm? What makes a customer prefer one firm vs its peers? What makes the firm deliver on this customer’s requirements better than its peers? Why is the competitive advantage sustainable in the face of disruptions and evolutions (i.e. longevity of a business)? The answers to these questions lie in a scientific and tangible understanding of the industry, the company’s business model and the softer aspects of the firm. There are several frameworks like the SWOT analysis (Strengths / Weaknesses / Opportunities / Threats), John Kay’s IBAS (Innovation, Brand, Architecture, Strategic Assets) etc. available which can act as a guide. Just like the industry growth drivers, the shape and size of a company’s competitive advantages changes over time. A scientific approach needs to recognise these changes. Saurabh Mukherjea’s book ‘The Unusual Billionaires’ (2016) gives a scientific approach that can be used to analyse the competitive advantage of Indian companies and changes in the same.

- Disruptions: The frequency of disruptions has increased across the world over the last few decades. More recently, in India, the frequency of black swan events has also increased – the last five years have seen demonetisation, GST, default by few large financial institutions, Covid-19, etc. Hence, understanding of the kind of disruptions that are beneficial for a firm (because market share gains become easier in the wake of a crisis) or those that are harmful is a very important aspect of fundamental research. For instance, a deep scientific analysis of the impact of the global financial crisis of 2008 (a global event) and the impact of demonetisation in 2016 (logistical challenge) can give an investor to better understand the impact of COVID-19 crisis, which is a combination of local logistical challenges and a global event. In our 1st May 2020 newsletter we had highlighted a framework to assess how well does a company use such events to disrupt their competitors despite the fact that such events can potentially topple market leaders. This framework is based on characteristics such as a) lack of complacency / lethargy; b) capital allocation to innovation; c) focus on systems & processes / tech investments; d) superior employee culture; and e) control on customers, distribution partners and manufacturing processes.

- Valuations: Whilst the mechanical aspects of a stock’s valuation can be dealt with by using mathematics, assumptions around longevity and strength of cash flows are an outcome of scientific understanding of the three bullet points mentioned above. For instance, in our 4th January 2020 newsletter, we had highlighted that whilst it is impossible to accurately forecast the future of any business, an investor can use tools – like: a) accounting forensics; b) sustainability of the moats of an organisation; and c) understanding the DNA of a business – to better predict the longevity of a business. And since the conventional DCF value significantly undervalues longevity, adding 8-10 years (or longer) to the ‘sustainability’ of moats in an investor’s expectation can lead to a substantial increase in the intrinsic value of some very high quality businesses.

- Investment philosophy: This includes the intended risk-reward outcome of the portfolio through a certain concentration (number of stocks), sectoral allocations (what types of stocks), length of holding periods, allocations, position sizing etc. A scientific approach towards deepening the understanding of an investment philosophy could involve back-testing or historical analysis of the risk-reward outcome. Great investors like Warren Buffett have evolved their investment philosophy over time as their understanding or an ever-evolving world around them has changed. For instance, prior to the 1970s, Warren Buffett’s approach was similar to that prescribed by Benjamin Graham i.e. buy decent (not necessarily great) businesses at a significantly cheap price, with focus being more on price than on the quality or longevity of the business. However, after the 1970s, Warren Buffett’s approach was more akin to those prescribed by Phil Fisher or Charlie Munger i.e. buy the highest quality businesses, focus more on their longevity (and less on getting a significantly cheap price), and stay invested in these businesses for a very long period of time.

Investment implications

Clarity of thought in equities investing is perhaps the most critical factor that can help investors meet their investment objectives. Just like humans have developed several mathematical and scientific tools to improve our ability to understand the world around us, investors need to follow the same approach in equity investing. Decisions based on myths or one’s personal beliefs exposes an investor to more luck than skill. Instead, a rigorous hunt for mathematical and scientific tools helps reduce the contribution of luck, and enhances the probability of success in equity investing.

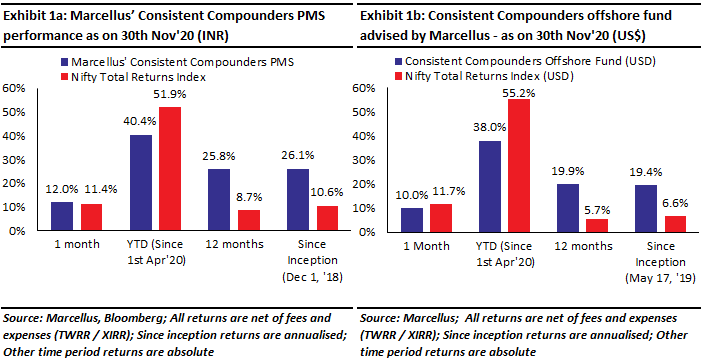

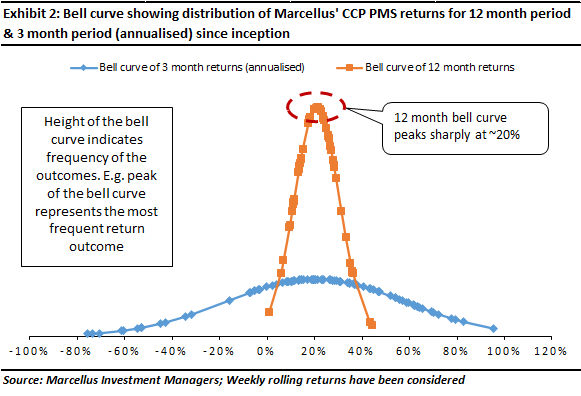

At Marcellus, our team of 11 analysts use several frameworks – like our succession planning framework, lethargy framework, longevity based valuation framework – and several other mathematical tools and historical data crunches which we have articulated previously in our newsletters, blogs and webinars. These tools help us deepen and evolve our understanding of various elements of Consistent Compounding. The fruits of these effort can be seen in the bell-shape curved curves shown above which are based on the actual returns generated by Marcellus’ Consistent Compounders PMS since inception. As the chart shows, not only has CCP consistently gunned out returns of around 20% over a 12 month period, there isn’t a single 12 month period (on a weekly rolling basis) in which CCP has generated negative returns. |

|

|