In light of more than 300,000 deaths from Covid-19 so far, there is widespread despondency in India. This is compounded by the inability of almost everybody – barring the tech-savvy and the rich & the powerful – to get a Covid-19 vaccination slot. The situation has worsened because Indians are hearing from friends and relatives from across the world, that the developed world is vaccinating itself rapidly and life there is returning to normal gradually.

Patronising views regarding India have never been in short supply. For example, “India,” Winston Churchill once barked, “is merely a geographical expression. It is no more a single country than the Equator.” Churchill was rarely right about India….” (Source: “From Midnight to the Millennium” by Shashi Tharoor).

Lant Pritchett, a development economist, said over the decade ago, “I argue that India is today a flailing state—a nation-state in which the head, that is the elite institutions at the national (and in some states) level remain sound and functional but that this head is no longer reliably connected via nerves and sinews to its own limbs” (Is India a flailing state? Detours on the four-lane highway to modernization, 2009).

Mohan Guruswamy, a policy analyst, is of the view that “The record of the Indian State in improving the living standards of the majority of its people is abysmal” and “on all infrastructure indices we are well below – forget China – even that failed state, Pakistan” (Source: Deccan Chronicle, 2018).

However, is India really a flailing state? Has the country become the hell hole that it is being made out to be? Or are we suffering from “recency bias”, which is the tendency to place too much emphasis on experiences that are freshest in your memory—even if they’re not the most relevant or reliable (read more here), given the traumatic events of the past 12 months? Let us take a look at the data.

(Note: Like millions of Indians, we too have lost loved ones over the past year. While loss of every life is tragic, we have been trying – for ourselves as much for our readers – to contextualise the events we have lived through over the past year.)

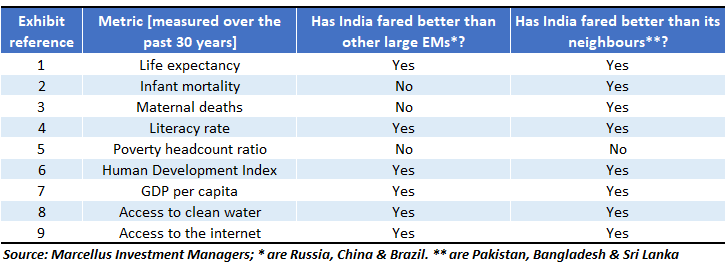

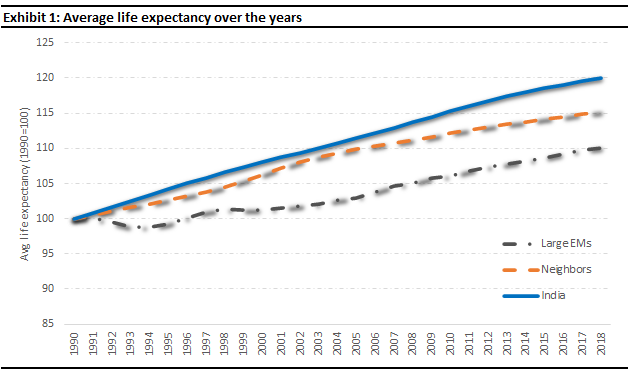

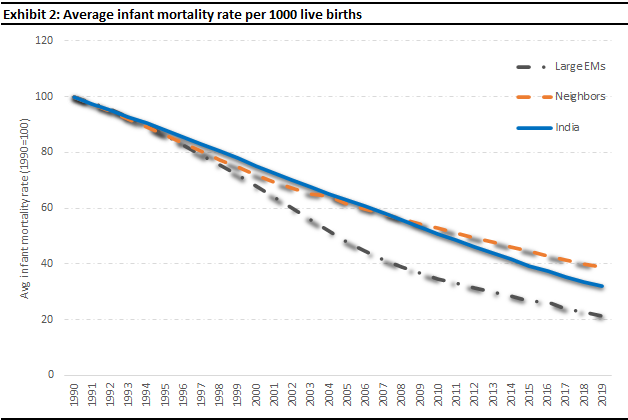

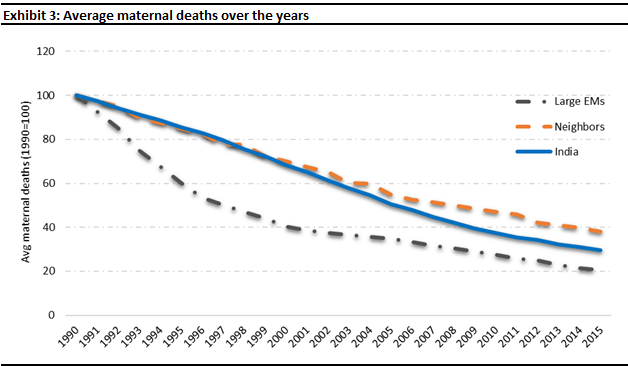

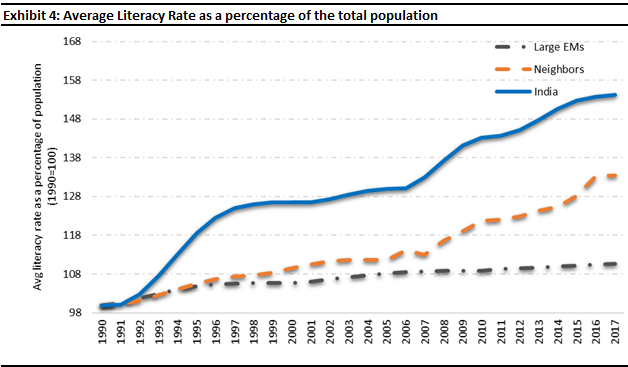

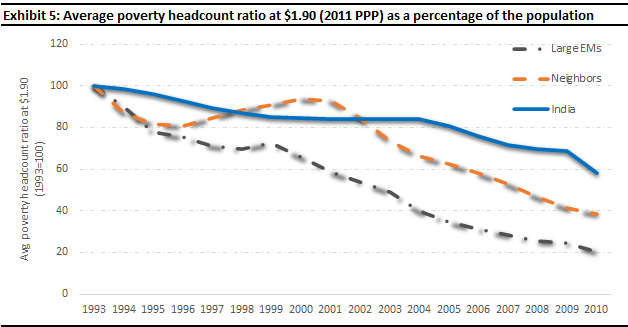

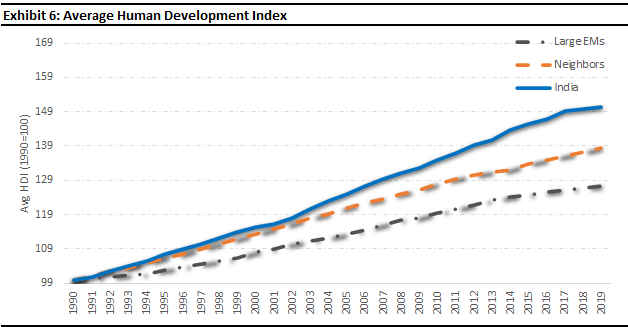

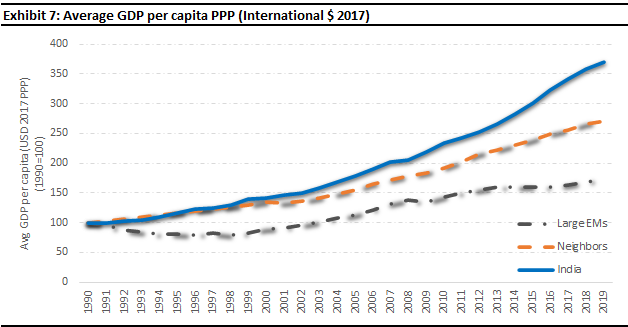

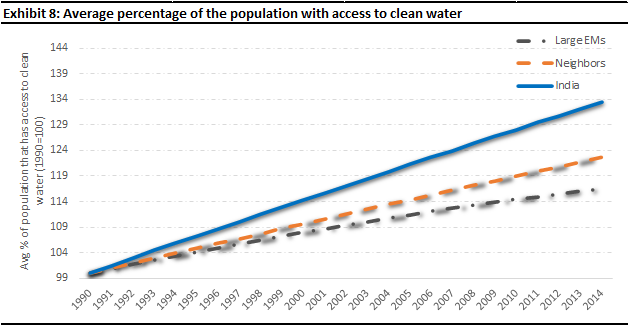

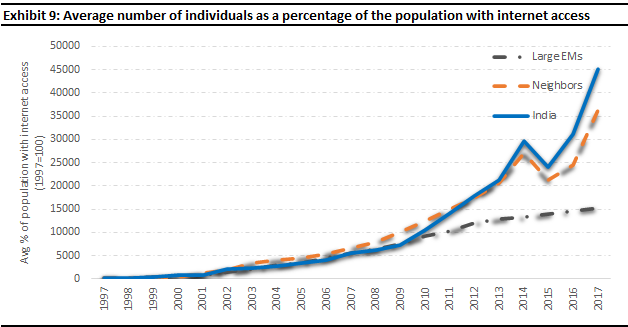

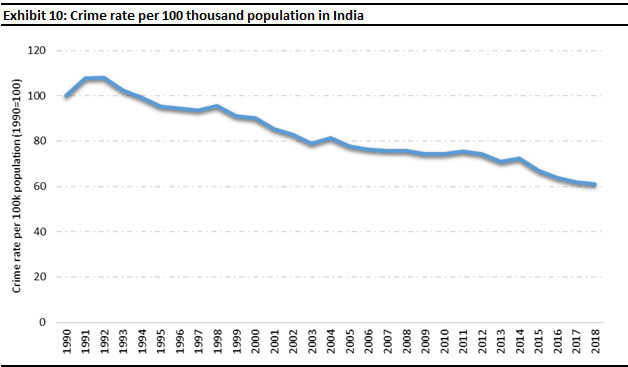

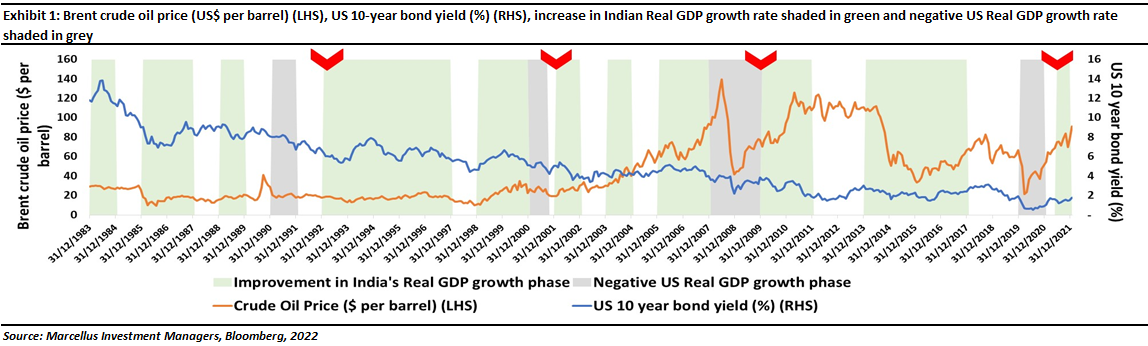

We analysed different metrics under broader categories like health, development, and social sectors. As shown in the charts below, in terms of the above indicators, India has improved steadily over the past 30 years. Most notably, India’s progress on these fronts has been, in general, superior to other large Emerging Markets (EMs) and to India’s immediate neighbours.

To compare India with other large EMs and its neighbouring countries, we chose 3 countries each under the large EMs (China, Russia, and Brazil) and neighbours (Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, and Pakistan) categories. Then we averaged the data under each of the metrics for both the groups (i.e., we averaged China, Russia, and Brazil for the “Large EMs” data series, and we averaged India’s 3 largest neighbours for the “Neighbours” data series). We then rebased everything to 1990 (wherever applicable) to build as accurate a picture as we could of India’s performance – relative to a range of other developing nations – on a range of indicators.

India’s performance on the health front has improved faster than one might imagine

Life Expectancy: Life expectancy at birth is the number of years a person is expected to survive. Exhibit 1 shows progress on this metric for India, large EMs and India’s neighbours