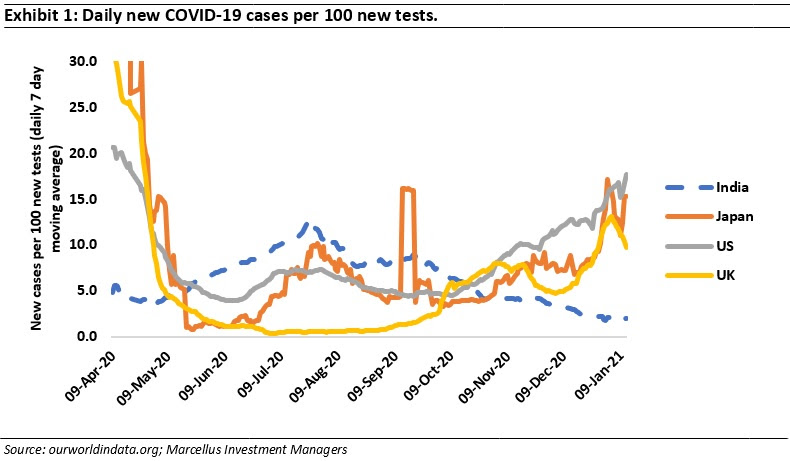

In fact, it is the rapid drop in cases per 100 tests in March/April 2020 that led the Marcellus team to conclude in early April 2020 that the COVID-19 threat was being radically overplayed – see Marcellus’ April 2020 blog. At a time when western ‘experts’ were saying that India will see in excess of 100 million COVID-19 cases (see alarmist study from CDDEP), the Marcellus team estimated that India’s case count was likely to be around 10 million. The method used by Marcellus team to arrive at this estimate is highlighted further on in this note.

Is the current euphoria around COVID-19 justified?

Given the chaos which we saw in 2020, it is remarkable therefore that now there is a sense of euphoria that we are past the worst of the damage inflicted by COVID-19. Part of this elation is due to the imminence of the vaccination drives which have been initiated globally. Yet if we look at the data shown in Exhibit 1, the most relevant metric – cases per 100 tests – has been rising for the advanced economies since October 2020 even as countries like India are showing a steady drop since July 2020. (Note: It is pointless to focus on total COVID-19 cases because as testing rises, so do total cases. A more useful metric is new cases per 100 new tests.)

So, after everything we have been through over the past year, how should investors really think about COVID-19? And how should we conceptualize the disease as we go about our day-to-day business?

Rational thinking helps

Firstly, we need to treat the grand claims (both pessimistic and optimistic) about COVID-19 (and other issues) with a degree of scepticism. In March 2020, three of the most alarmist studies around COVID-19 were published:

- A celebrated study by Imperial College likened the COVID-19 pandemic with the 1918 Influenza pandemic in terms of the severity (Imperial College study, 2020: Source – Imperial College website). This, it turns out, was a gross overestimation of the risk posed by COVID-19. The 1918 flu epidemic claimed 228,000 British lives (Deaths during 1918 pandemic, 2021: Source – Metro news). COVID-19 has so far claimed 82,00 British lives (British COVID-19 fatalities, 2021: Source – worldometers.info).

- The Centre for Disease Dynamics, Economics and Policy (CDDEP) along with John Hopkins University (who later pulled their name out – read more here) published a study about COVID-19 hitting India particularly hard and affecting more than 125 million people (Predicted infections from COVID-19, 2020: Source – CDDEP website). So far India has seen 10.5 million COVID-19 cases and given the trend seen in Exhibit 1, it seems unlikely that the CDDEP’s 125 million estimate will be the actual outcome.

Secondly, it is crucial to not get influenced by the recency bias – which makes a person give more value (fear) to information that he has come upon recently relative to what he learned a few years ago. For example, in 2018 in India, road accidents had a Case Fatality Rate (CFR = total deaths from recognized cases/total recognized cases) of ~32% (Road accidents statistics, 2019: Source – Autocar pro website) vis a vis the 1.44% CFR of COVID-19.

To understand the power of recency bias, let us frame the situation in a different way by taking numbers for the state of Maharashtra. 39 people were killed for every 100 road accidents in Maharashtra in 2019 (Road accidents in Maharashtra, 2019: Source – Highway police, Maharashtra government) vis a vis 3 people per 100 COVID-19 cases as of 31st December 2020 (COVID data widget, 2021: Source – GitHub widget for live tracking). And yet, if you look on the streets of Maharashtra, you will many people are riding their 2-wheelers with masks but without helmets!

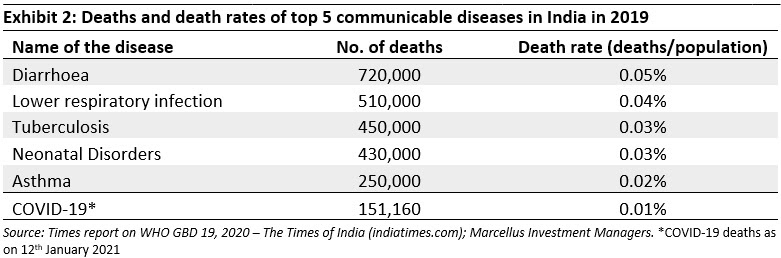

Similarly, tuberculosis, also an infectious disease, had a CFR in India of 17% in 2019 (TB statistics, 2019: Source – Worldhealthorg website) significantly higher than that of COVID-19 (1.44%) in India. In fact, when compared with other infectious diseases prevalent in the country, COVID-19’s death count (151,160) as well as death rate (0.01%) is the least compared to the top 5 communicable diseases in India, as evidenced in Exhibit 2.