“So we think in terms of that moat and the ability to keep its width and its impossibility of being crossed as the primary criterion of a great business. And we tell our managers we want the moat widened every year. That doesn’t necessarily mean the profit will be more this year than it was last year because it won’t be sometimes. However, if the moat is widened every year, the business will do very well” – Warren Buffet in Berkshire Hathway Annual Meeting (2000).

Our 1st June 2020 newsletter (CCPs avoid price hikes to strengthen pricing power) highlighted that, “The standard definition of high pricing power is the ability of a firm to hike product prices without witnessing attrition in its customer base. However, since most business battles are fought around price cuts, we believe the complete definition of pricing power should be as follows: If an incumbent firm offers a product to its customers at a certain price (say Rs 100), and a new competitor decides to offer a similar product to the same customers at a lower price (say Rs 70) – then can the incumbent retain its Rs 100 product price and also retain its market share? Or will the incumbent need to cut its product prices to defend its dominance? If it is the former, then the incumbent has high pricing power, otherwise not”.

For instance, we saw Patanjali mount a conventional price war in 2015 to attract new customers. In such a price war, dominant incumbents with weak pricing power struggle to protect their market share. However, companies which have built strong barriers to entry around their businesses, end up protecting both the market share as well as their profitability. So how can an investor identify the prevalence of such strong barriers to entry?

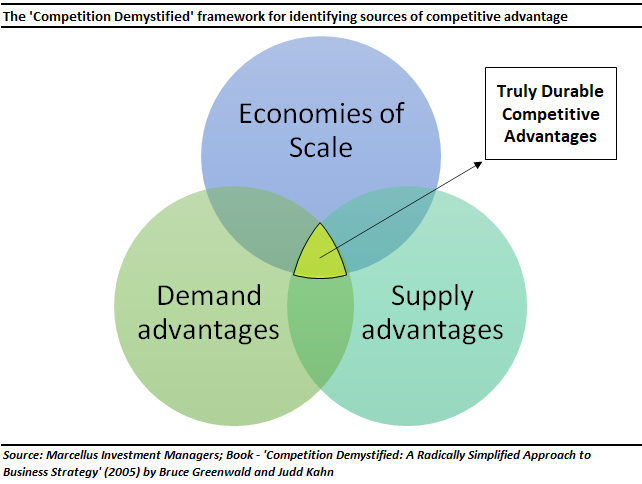

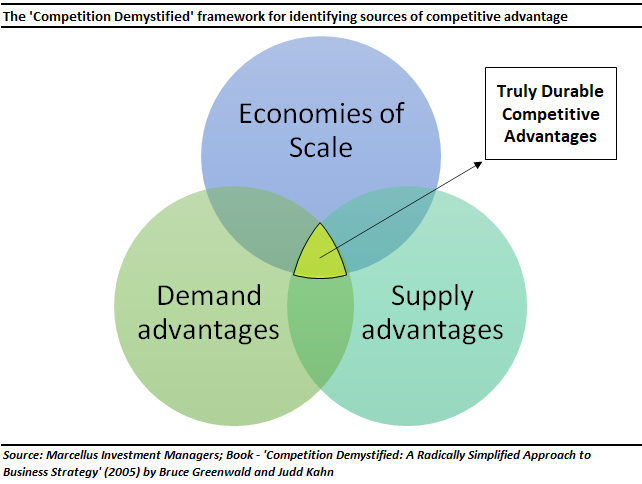

In the book ‘Competition Demystified: A Radically Simplified Approach to Business Strategy’ (2005), authors Bruce Greenwald & Judd Kahn suggest that there are three genuine sources of competitive advantage which result in barriers to entry: Supply side advantages, Demand side advantages, and Economies of scale. Whilst it is easy to build standalone sources of competitive advantages in each of these areas, truly durable competitive advantages arise from the interaction of supply-and-demand advantages, and from their interplay with economies of scale.

Identifying sources of competitive advantage in Indian small-ticket consumption

Supply-side advantages: A supply-side advantage is one where a firm can make or deliver products cheaper and more efficiently compared to its competitors. For example:

- Distribution: It is estimated that India has almost to 10-12 million kirana/grocery shops because of its highly dispersed population marked with poor transport infrastructure, and diverse demand patterns across geographies, and socio-economic strata of households which results in high number of SKUs. Hence, establishing a fragmented distribution network across the country and managing the transport and delivery of a high number of SKUs whilst providing supply chain efficiencies (or inventory turns) to the channel partners is one of the biggest challenges which, if addressed, can create massive barriers to entry. Another type of distribution challenge is that a typical kirana / grocery shop has limited shelf-space and capital constraints. A short-term replicable solution is to offer higher margins to the channel partners. However, the more sustainable entry barrier is to either create such a strong customer-pull for your products that the kirana is compelled to give preferred shelf space to your products, or offer higher inventory turns (which are difficult to replicate by competitors). Asian Paints has famously adopted the latter approach to build an almost invincible paints franchise in India.

- Proprietary technologies / Patents / Trade Secrets: Proprietary technology / Patents / Trade secrets are intangible sources of competitive advantage which makes the product difficult to replicate for a competitor. In India, there are no famous examples where proprietary technology or patents have led to a significant competitive advantage in small-ticket consumption mainly because of the challenges around securing and enforcing patents rights in India (as discussed in this blog by a lawyer: link). A few examples of some of the best-kept trade secrets in Indian FMCG are Coca-Cola’s Coke formula, Nestle’s Maggi Masala or the ‘WD-40 anti-rust/lubricant’ distributed by Pidilite in India.

- Procurement: Procurement advantage can be around consistent availability of raw material which is not available to competitors or sourcing raw materials at a cost lower than competitors. Although there is no raw material which is exclusively available to certain companies, some companies have built advantages around procurement by establishing a back-end supply chain which bypasses intermediaries and directly procures from farmers/producers. One such example is Marico which disintermediated the copra supply chain (which is the main raw material for Parachute coconut oil) and started sourcing directly from farmers/individual traders by setting up collection centers in Kerala & Tamil Nadu. Marico further improved direct procurement itself through the use of technology to enhance transparency for farmers, reduce the procurement cost and also avoid supply disruptions.

- Regulatory hurdles: Regulatory hurdles such as licenses, restrictions, strict quality standards, etc increase the cost of entry and either prevent the entry of new firms or make it unattractive for new firms to enter the market. For example, in categories such as Infant Nutrition, manufacturers are prohibited from advertising. This makes it difficult for new players to challenge the incumbents, Nestle and Abbott.

Demand-side advantages: A demand-side advantage is one where a firm has superior access to the customer or customers are captive to the firm’s products. More loosely, demand-side advantages create pull-based demand for the firm’s products. Commonly seen demand-side advantages for dominant companies in small-ticket consumption are:

- Brand: A strong brand creates a distinct identity for the product, signals quality & legitimacy and gives the manufacture leverage over the distribution network where shelf space is a limited resource. Advertising on TV and print media has been the most common route of brand building for FMCG companies. With media advertising being expensive in India, it takes a lot of money, innovative content, and perseverance to build brands and maintain them. Nirvana is attained when the brand becomes synonymous with the category itself – for instance, Maggi for noodles, Colgate for toothpaste, etc.

- Product differentiation: Product differentiation is another way to build a brand. A product can be differentiated either due to its unique characteristics (such as the unique taste of Maggi noodles) or superior product quality – relative to competitors – in products where quality/durability/comfort matters to customers (such as Relaxo’s Hawaii chappal or Jockey’s innerwear). We have seen that a superior product creates a degree of customer captivity as long as the product’s pricing is competitive.

- Switching costs: Switching costs generally arise where the product is either critical/crucial for the customer or where uncertainty/cost of switching is higher than the benefit of switching. Interestingly, whilst brand can be used to create switching costs (eg. it is difficult for parents to shift their kids from Cerelac to alternative cereals for toddlers), other types of switching costs arise from ‘systems competition’ (eg. the use of cheap razors and expensive blades by Gillette).

- Influence via intermediaries: There are markets where customers pay for the product, but he’s not directly involved in the purchase, generally because he lacks the ability to gauge the effectiveness/quality of the product. In such markets, companies which establish a deep relationship with intermediaries (eg. plumbers, carpenters, electricians) by arranging trade meetings for new products/new features/application techniques. An additional tactic used to influence intermediaries is to reward them with loyalty schemes/points. For example, Pidilite created demand for its products by targeting carpenters/masons/contractors and educating them about the benefits of these products and their application process.

Economies of Scale: If the cost per unit of product sold decreases as the volume increases, a company gets stronger as it gets larger. If such a firm passes on the scale benefits to the customers either through lower price hikes (or by avoiding prices hikes), it becomes very difficult for other firms to compete with the market leader. For example, Relaxo enjoys substantial scale benefits in advertising expenses where it spends ~Rs 80-90crs a year by hiring top Bollywood celebrities, but because of its high sales volume of 190 mn pairs/annum (1.5-2x larger than any other firm in India), the cost of advertising per pair is merely ~Rs 5 per pair. Relaxo enjoys a similar scale benefit in procurement and distribution. As a result, at the economy end of the footwear market, where affordability and quality matter the most, a new entrant will find it almost impossible to compete with Relaxo.

Related to economies of scale are Network Effects where value of a product increases as more people use it. Both become powerful with scale. Well-known examples of network effects are firms like Facebook, eBay, etc. The indirect network effect is where the larger the company grows, the greater is the data collected. This data is then mined to improve the customer experience of existing customers as well as to acquire new customers. For example, Asian Paints uses proprietary historical demand data and the real time data coming from its ~50,000 tinting machines to accurately forecast demand for their products for every nook and corner of the country, for each day in a year. This helps Asian Paints delight the painters and paint dealers with ready availability of several thousand SKUs in a highly voluminous product category and offer substantially better inventory turns (3-4x better than the competition) to them.

Investment Implications

Whilst the framework of supply, demand and economies of scale remain the same, barriers to entry created within this framework need to keep evolving / deepening over time due to the disruption of aspects like consumer behaviour, supply chains, modes of understanding and influencing a consumer, type of competitors, etc. For instance:

- Offline distribution related efficiencies has been a major source of competitive advantage historically in India. However, e-commerce is rapidly improving the ease of distribution reach, creating supply chain efficiencies, and offering infinite shelf space to new brands. B2B aggregators such as Udaan, Jio B2B, etc are helping to build the offline distribution by disintermediating the existing system of C&F agents, distributors, wholesalers. Modern-retail formats are replacing the traditional mom-n-pop outlets leading to consolidation of distribution touchpoints. As a result, the cost and time involved in establishing distribution is reducing for manufacturers.

- The attention span of consumers is shifting from the TV & print to digital media resulting in the rise of digital advertising which has made it easier to build brands online without the need to have large advertising budgets for mainstream media.

- The product differentiation benefit between branded and local/unorganised players vanishes in markets where all competitors have become organised/branded. For example, more than 90% toothpaste market is now dominated by organised branded players such as Colgate, HUL, Dabur and Patanjali with no substantial difference in product quality.

Hence, whilst advertisement and distribution were one of the major barriers to entry created by incumbent dominant players by using their economies of scale, technology has started to disrupt these competitive advantages. Similarly, with the cost of capital going down across the world, access to large pools of capital for new entrants is reducing the barriers to entry around marketing & distribution. Furthermore, the formalisation of the economy is increasing the uniformity in consumption habits and hence reducing the barriers to entry around product differentiation, localisation, etc.

A company with static sources of ‘competitive advantage’ will therefore face erosion of its pricing power. Therefore, an investment strategy based only on the current barriers to entry is no longer sustainable. Instead, investors need to assess whether their investee firms use technology to build/strengthen existing supply-side or demand-side competitive advantages or build new ones. See our 1st October 2020 CCP newsletter on this subject (The Role of Technology in Consistent Compounding).

For example, Pidilite’s new rural initiative is a combination of supply-side and demand-side advantages. The company is re-branding the currently underserved multi-brand outlets in small villages with population less than 12,000 as ‘Pidilite Ki Duniya’ stores. The firm is not only offering small village stores a range of Pidilite products but also using such outlets as points to connect with the local masons/contractors to make them aware about the product’s uses and the relevant application techniques. Pidilite has opened ~5,000 such stores across villages in India and the firm’s division which caters to small towns and villages formed ~30% of Pidilite’s consumer segment sales in FY20. Pidilite’s ability to consistently strengthen its competitive advantages decade after decade means that its Free Cashflow per share has compounded at over 25% per annum over the last 18 years!

Note: Pidilite, Relaxo, Nestle and Asian Paints are part of many of Marcellus Investment Managers’ portfolios.

Deven Kulkarni is part of the Investments team at Marcellus Investment Managers (www.marcellus.in).